When BIL met CIL

First some introductions.

The Battery Imaging Library aka BIL is a growing open, curated collection of multi-modal, multi-length scale battery imaging datasets – from lab and synchrotron X-ray CT to neutron CT and electron microscopy – all wrapped in a FAIR-compliant, searchable platform.

The Core Imaging Library, aka CIL is an open-source Python framework for inverse problems, in particular tomographic imaging and mathematical optimisation.

So far so good: one project gives us rich, real-world battery data; the other gives us powerful tools to do something meaningful with it.

All we have to do now is to find a nice way to talk to each other.

Our Admitted Inverse Crime

With today’s tools, it’s almost effortless to:

- find a tomography-related image, e.g., a Shepp–Logan phantom

- define an acquisition geometry, i.e., a sinogram space with specific detector points and angles

- define the forward operator (Radon transform) and generate the corresponding sinogram

- apply some noise to the sinogram

- and test your favourite analytic and iterative reconstructions algorithms.

However, this is a textbook example of an inverse crime: we generate synthetic data with essentially the same forward model, assumptions, and discretization that we later use for reconstruction. The geometry is exact, the physics is idealised, the noise is usually “nice” and the only real difficulty left is then numerical optimisation. Certainly, this approach is useful and even necessary for early-stage development: it validates that the code runs and that the algorithm behaves as expected under ideal conditions.

But let’s be honest: this is still a long way from real applications. Real experiments aren’t neat phantoms; they involve long scans, mechanical drift, misalignments, imperfect flat- and dark-field corrections, low SNR, beam instabilities, and datasets on the order of tens or even hundreds of gigabytes. If we want our methods to matter in practice, we have to step out of the Shepp–Logan comfort zone.

Enter BIL

That’s where BIL comes in. Instead of toy problems, we get about 3.4 TB of multi-modal, multi-length scale data, with real noise and artefacts. This is perfect for testing reconstruction algorithms and pipelines on something much closer to reality.

But there’s a catch. Those datasets don’t arrive as a nice clean NumPy array with one-line “load me” function. They come from different scanners, beamlines and instruments, each with its own way of storing projections, darks and flats, rotation angles, geometry and experiment metadata.

To really make use of BIL inside CIL, we need to read and interpret this metadata correctly. That’s where DataReaders come in.

CIL CT Data Reader Hackathon

Recently I participated in a hackathon focused on one simple task: to implement and improve CT DataReaders for different scanners and data formats, and to hook them up cleanly inside CIL. This event was organised by the Collaborative Computational Project in Tomographic Imaging.

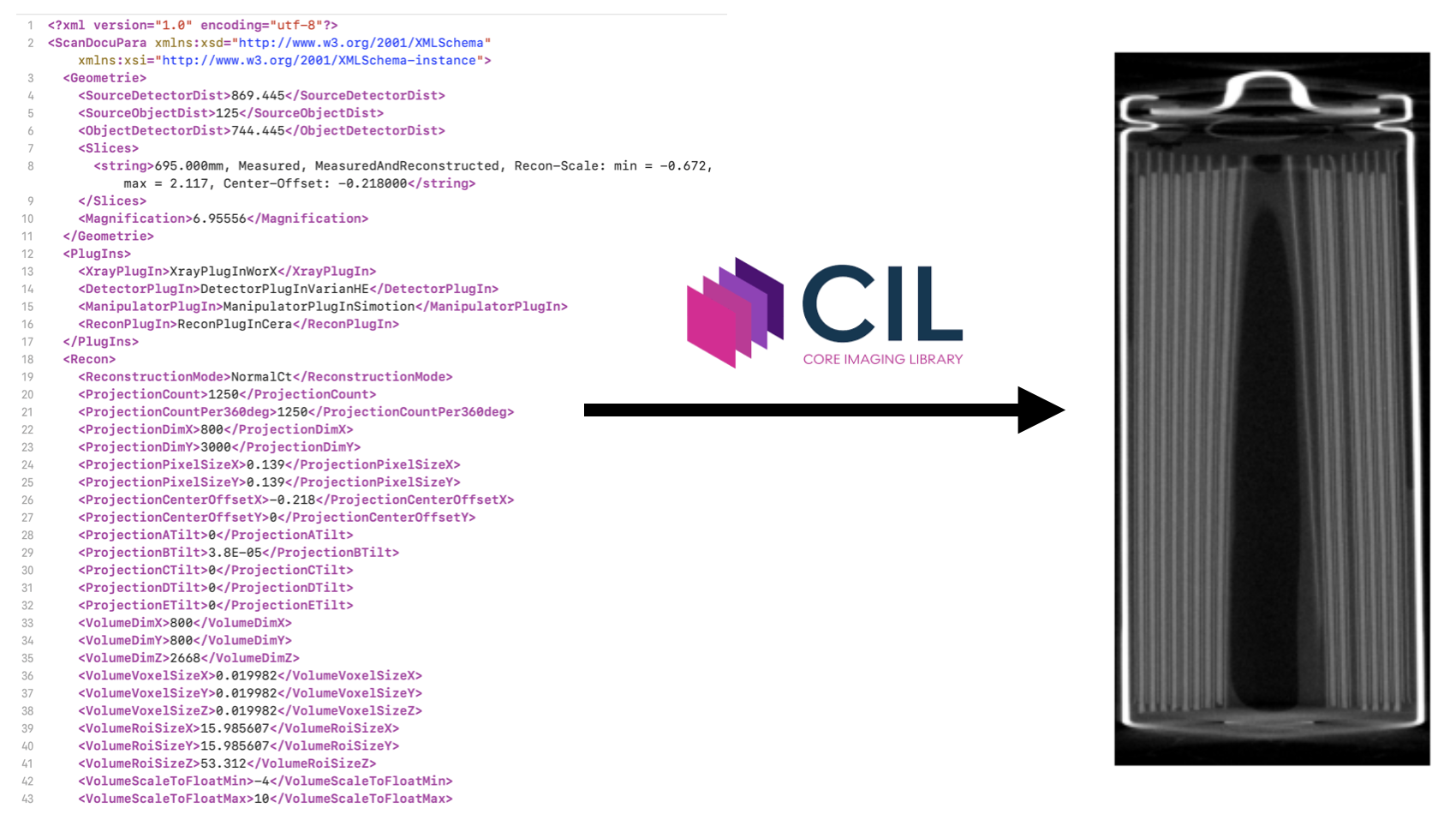

The goal was to implement CIL DataReader classes that:

- read the raw projection data and the associated metadata,

- set up the correct acquisition geometry, and

- perform an analytic reconstruction (FBP/FDK) that can be directly compared to the vendor’s own reconstruction.

During the hackathon, Dr. Kubra Kumrular and I worked on the Diondo D5 data reader. We tested our implementation on a AAA NMC532 Li-ion battery data which are available from BIL. Data were acquired at MuVIS X-ray Imaging Centre at the University of Southampton using a Diondo D5 X-ray CT instrument.

- Raw Data: https://zenodo.org/records/17167576

- Vendor Reconstruction: https://zenodo.org/records/17167562

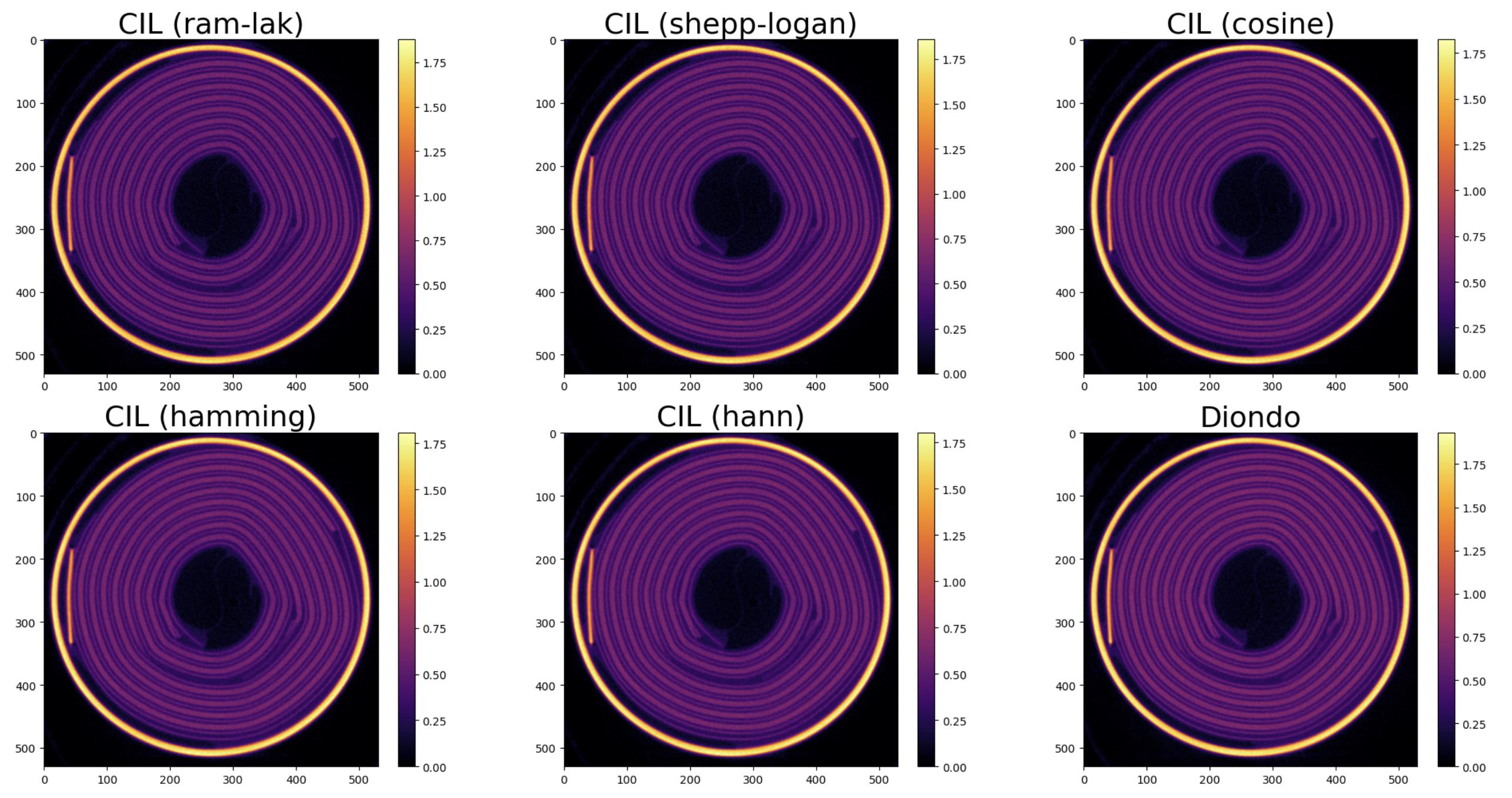

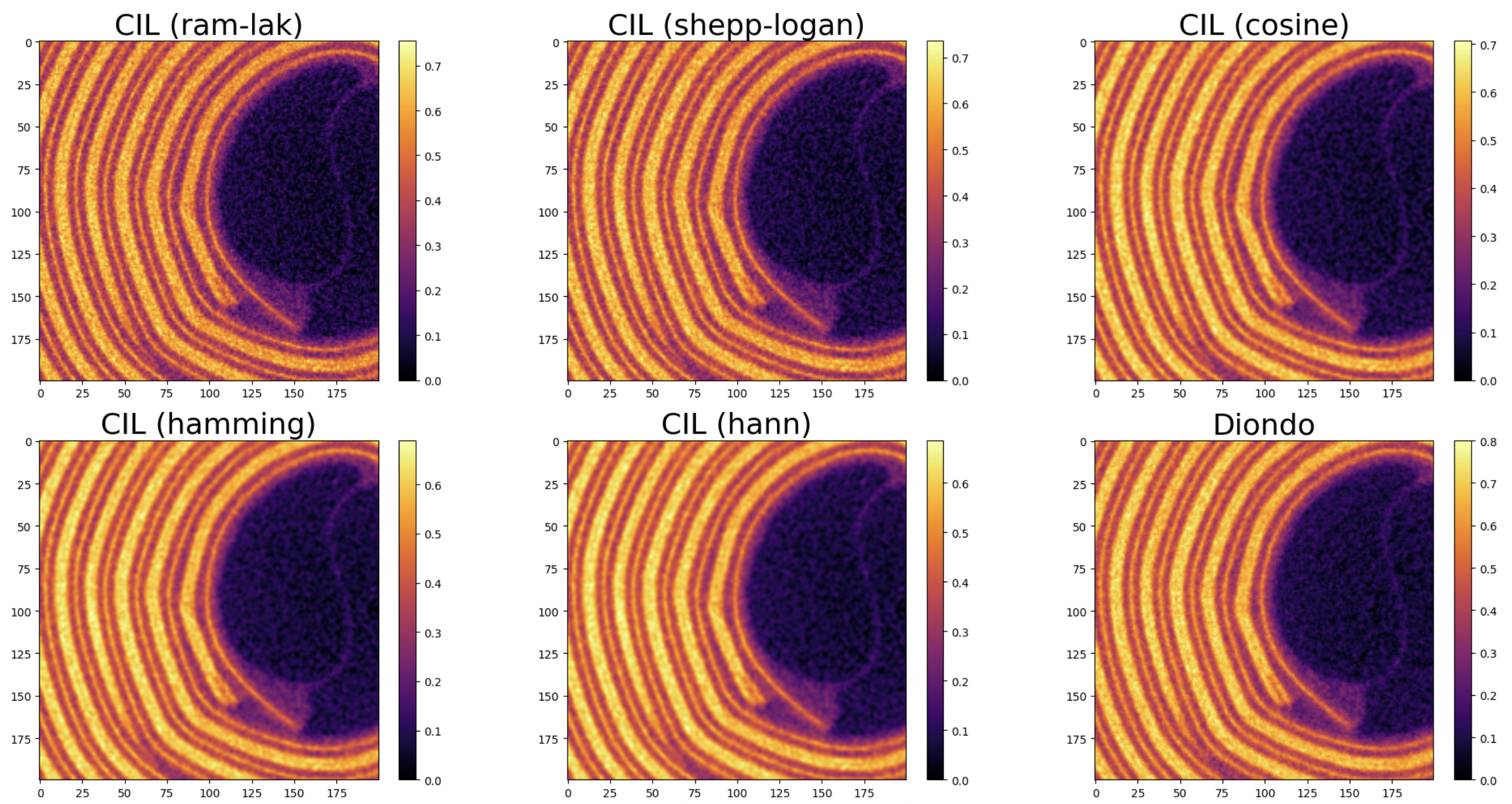

Our submitted jupyter notebook can be found CIL-Reader-Showcase -Diondo. As we observe above the CIL reconstruction is very similar to the reconstruction obtained by the vendor. Below is the 3D battery sliced through the middle.

Other participants developed readers for additional data formats, including

Because BIL already hosts some datasets produced by these acquisition systems, these readers can also be used directly in CIL to load and explore the corresponding data.

Conclusion

Having these DataReader classes in place is crucial: without them you end up digging through metafiles, guessing inputs, and rewriting the same loading scripts over and over. With them, you can skip the low-level file-format hassle and spend your time where you actually want to be – testing and developing iterative reconstruction algorithms on real experimental data, for example.

These readers are planned to be merged into the CIL master branch and maintained as part of the project, so they will stay aligned with future developments. In the meantime, we’d love for you to try them out on your own data and let us know what you think, what works well, and what could be improved.